Evaluating the Performance of Private Investment Strategies

Written by Kristy LeGrande, CFA and Natalie Miller, CFA

Measuring returns is essential for evaluating the success or failure of an investment program. At first glance, this seems like a straightforward exercise. However, return measurement becomes increasingly complex when looking at less traditional investments, such as private equity or private debt.

Time-Weighted Returns

Many investors are familiar with time-weighted returns (TWR), even if they do not know the concept by name. A typical public market investment, such as an S&P 500 Index mutual fund, will show TWR as the fund’s performance metric. The simplest way to calculate a time-weighed return is to take the return for multiple continuous time periods (often daily or monthly) and link them together. This results in a compounded return.

Exhibit 1: TWR Formula.

One important feature of TWR is that it does not account for the effect of cash flows in investment performance. This approach makes sense when evaluating a public investment. A public fund manager typically cannot control the timing of cash flows, as investors can trade in and out of these investments daily, if not more frequently.

Private Market Investments

Private market fund managers, however, do control the timing of cash flows. A standard private market fund, such as a private equity or private debt fund, will use a drawdown structure to fund its investments. Within a drawdown structure, the fund manager raises a specific amount of capital, known as “committed capital.” Over several years, the fund manager will “call” capital at various times. When a manager calls capital, the investor must send some or all of their committed capital to the manager, with the manager determining the amount. Additionally, the manager decides when to sell investments and return money to their investors – but investors cannot choose when to sell their investments.

So, in a typical private market fund, the fund manager has control over the cash flows of the portfolio.

Internal Rate of Return

When a manager determines the timing of cash flows in a portfolio, we want to capture the impact of those decisions on the investment. It is an active investment choice made by the fund manager. This is why many investors prefer an internal rate of return (IRR), also known as dollar-weighted returns, to evaluate the performance of private market investments. Unlike TWR, IRR accounts for the timing and magnitude of cash flows in a portfolio.

Exhibit 2: IRR Formula

Drawbacks of IRR

While IRR’s reliance on cash flows to calculate return makes it a useful metric, this reliance can also be a disadvantage. Because IRR is sensitive to both the timing and magnitude of cash flows, large distributions early in a fund’s life can have an outsized impact on a fund’s IRR.

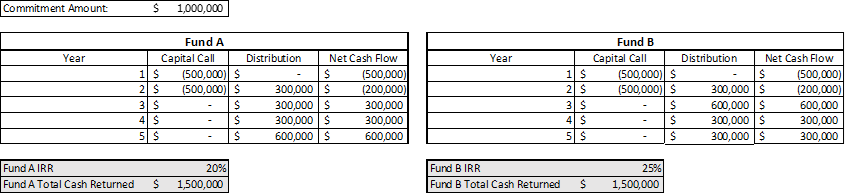

For example, take two funds, each with a commitment amount of $1,000,000. Fund A’s largest cash distribution occurs later in the fund’s life. Fund B’s largest cash distribution occurs early in the fund's life. Both funds return a total of $1,500,000. However, Fund B’s IRR is significantly higher than Fund A’s:

Exhibit 3: Sample IRR calculation 1

Additionally, IRR assumes that any cash flows are reinvested and earn a rate of return equal to the IRR. Using the example above, IRR assumes that the $600,000 cash flow from Fund B in Year 3 can be reinvested and earn 25%. This assumption rarely holds true in practice.

Final Thoughts: Using IRR Alongside other Return Metrics

As with any evaluation metric, IRR has both advantages and drawbacks. For this reason, it can be helpful to evaluate an investment’s performance using a variety of other return metrics. One answer can be TWR if an investor’s private market investment program is not experiencing large swings in cash flows. If the program is mature, IRR and TWR will eventually converge. However, divergence will occur again should there be significant cash flows in or out of the private markets program. Therefore, it can be difficult to compare TWR and IRR.

Instead, it is best to take a holistic approach and evaluate various multiples, such as total value to paid-in capital, in addition to IRR. For example, total value to paid in capital measures the sum of a fund’s total cash distributions and remaining value divided by the total amount of capital paid into a fund. This metric is useful for evaluating the growth of a dollar in a particular fund. Considering IRR along with other cash multiples allows an investor to consider both the impact of the manager’s cash flow decisions and the overall growth of their investments that come from a manager’s thoughtful acquisitions of and improvements to underlying assets.

Additionally, investors should be mindful of the time frame in which they are evaluating returns. While monitoring short-term investment results is important, investors should be aware that meaningful performance evaluations of private investments require longer time periods, usually at least five years.